|

Abu Hasan Ali ibn Naif, better known as Zaryab (789-857 AD) was one of the most famous musicians and teachers in Cordoba in Islamic Spain. According to Shoja el-Din Shafa in his well-researched book, “Iran in Islamic Spain,” Zaryab came from the Fars province of Iran, and later moved to Baghdad. He achieved great fame in the Abbasid Court in Baghdad as a student of the renowned Iranian musician and composer, Ishaq al-Mawsili. A polymath, Zaryab had knowledge of astronomy, geography, meteorology, botanic, cosmetics, music, culinary arts and fashion. He left Baghdad, traveling first to Syria and then to Tunisia, after which he was invited to Al-Andalus by the Umayyad prince, Al-Hakim (ruled 796-822). He settled in Cordoba and soon began to introduce standards of excellence in food, fashion and music. He established a school of music which taught both male and female musicians who would influence Andalusian music for generations. He is also considered the founder of the Andalusian musical traditions of North Africa. He is said to have improved the Oud by adding a fifth pair of strings. He dyed four strings in a color that symbolized Aristotelian humors and the fifth string was to represent the soul. According to Henri Tarrasse, a French historian, legend attributes winter and summer clothing styles and the “luxurious dress of the Orient” found in Morocco today to Zaryab. It has been said that he created a new type of deodorant to get rid of bad odors and promoted morning and evening baths, emphasizing the importance of personal hygiene. He is said to have invented an early toothpaste which he popularized throughout Islamic Spain. He changed the local cuisine by introducing new fruits and vegetables like asparagus and popularized shaving among men and using salt and fragrant oils to wash hairs. Zaryab is said to have revolutionized the court at Cordoba and made it the stylistic capital of its time, changing it for generations to come. Through the genius of men like him, for a span of two generations, Cordoba was the finest, most glittering metropolis in all of Europe. Resources:

Mahsati Ganjavi was a world renowned 12th century Persian poet. Not much is known about her life, except that she was born in Ganja in Aran in today’s Republic of Azerbaijan and that she was highly esteemed at the court of Sultan Sanjar of the Seljuk dynasty.

We also know that she spent important periods of her life in Balkh, Marv, Nishapur, Herat and Marva and that she associated with the great poets of her time, Omar Khayyam and Nizami. Her free way of living and verses have stamped her as a Persian Madame Sans-Gene and her love affairs are recounted in the works of Jauhari of Bukhara. Her courageous poetry reflected women’s dreams of freedom and equality. Her poetry condemned religious obscurantism, fanaticism and dogma for which she was eventually persecuted. She organized literature circles for women to help them learn and work together. She was considered second best only to Omar Khayyam in her mastery of quatrain. The most complete collection can be found in the book of Nozhat al-Majales. Her unsurpassed talent and free-thinking for her time, gave rise to many myths and legends. The 900th anniversary of her work was celebrated by UNESCO in 2013, and in 2016, a monument was unveiled in her name in the French city of Cognac. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sources:

Mehrangiz Manouchehrian (1906 – 2000 AD) was both Iran’s first female lawyer and first female Senator. She was a lawyer with tremendous command of the materials of law; a feminist who fought relentlessly against discrimination; and was highly respected by the authorities and her peers in the Senate. It was during the time when the Pahlavi government strove to give women’s more rights, that using her experience as a lawyer she drew up the Family Protection Act, one of the most progressive of its time. The conservative clergy did not approve of her proposed bill, not only because they claimed it was against Islam, but because they wished to preserve their power and material advantages which they gained by their involvement in the affairs of the family. They called her a heretic and traditional forces in the society threatened her. In fear for her safety, Mehrangiz fled Tehran for some time. It was only later, with the effort of more women, who convinced the parliament and leveraged modernist religious jurists, that the bill became law under the name of the Family Protection Act of 1967. It underwent further changes in 1975 to conform better to the interests of women.

The law contributed to women in various ways such as increasing the minimum age of marriage to 18 and allowing them to ask for a divorce. Prior to the 1975 law, a man could marry up to four wives but because of this bill, he could not marry a second wife without the consent of the first and marrying a second wife constituted sufficient cause for a woman to divorce her husband. When Mehrangiz spoke publicly in the Senate against a law that forced women to get their husband’s permission before traveling abroad, Prime Minister Sharif-Emami insulted her. Exasperated, Mehrangiz finally resigned. Sharif-Emami later apologized to her privately, but she demanded a public apology which he refused. Mehrangiz Manouchehrian was awarded the United Nations Prize in the Field of Human Rights in 1968 for promoting women’s rights. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the Family Protection Law was revoked, and Iranian women lost all the rights that they had fought for. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ References:

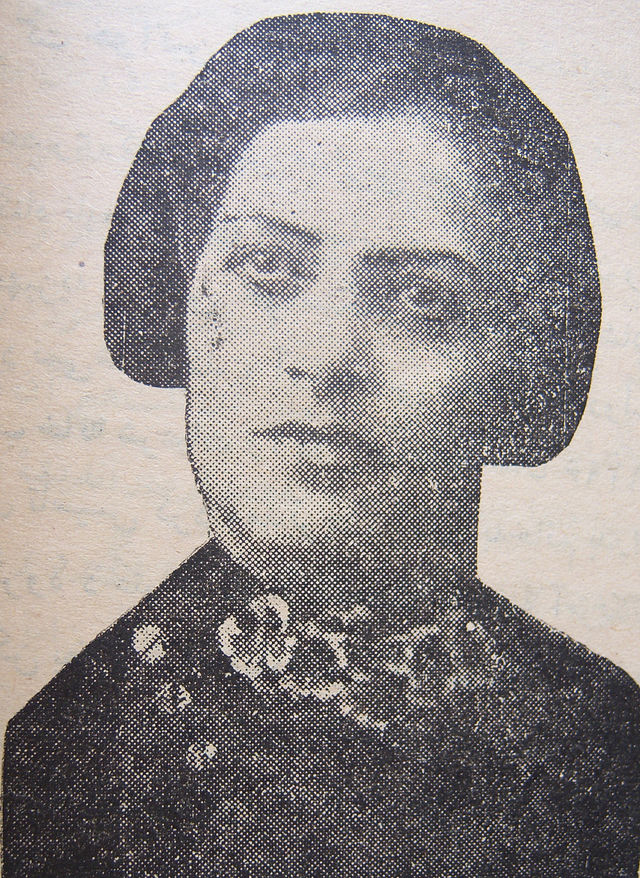

Mehrangiz Dowlatshahi (1919 – 2008 AD) was the first Iranian female ambassador before the 1979 Islamic revolution, who dedicated her life to fighting for women’s rights. She held several significant positions including being one of the first female members of parliament.

She was born to a powerful and established family. Her mother was of the renowned Sadeq Hedayat family and her father was a progressive man who believed in equality between men and women. He was in fact one of the few men who had encouraged Reza Shah to end compulsory veiling. Mehrangiz attended a high school run by American missionaries and graduated in 1936 when she was only 15 years old. Even before Reza Shah banned the veil, she and some other students, would refuse to wear the veil and bravely appear in public wearing a hat. Her father died before he could send her to Europe to further her education and her grandfather was a much more traditional man who was against sending a single young girl to Europe. He finally allowed her to go in the company of relatives. Mehrangiz studied in Germany and received a PhD in social and political science from Heidelberg University. Upon returning to Iran, she worked for several social services organizations. Eventually she established the Rah-e No (New Way) Society, which offered adult literacy programs and advocated equal rights for women. She served as a member of the parliament from 1963 to 1975 and contributed significantly to the passage of a new family law especially regarding women’s rights to file for divorce, which until then (as it is now again) a monopoly right of men. The Pahlavi government had to act with caution since it did not want to anger the clergy and bring about a political crisis. Finally, she became the first woman ambassador of Iran. After the 1979 revolution she moved to Paris where she published a book titled “Society, Government and Iran’s Women’s Movement.” She died in Paris in October 2008. ------------------------------------------------------- References:

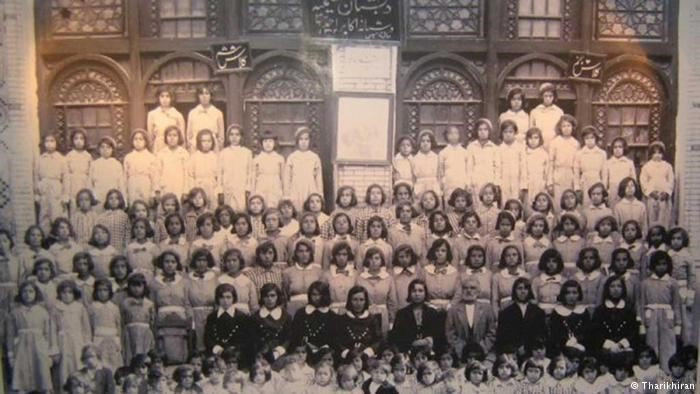

Tuba Azmudeh (1878-1936 AD) was an educator from a middle-class Iranian family who established one of the first schools for girls. Before the 1905 Constitutional Revolution, women had no rights, child marriages were common, and husbands could divorce their wives at any time. The discrimination was so entrenched in society that women had internalized and accepted it. Female education was against Islam and many believed that women didn’t even have the ability to learn. In the early days of the Constitutional Revolution, a few women activists emerged. One of these was Tuba Azmudeh, who founded a girl school called Namus (Honor). Like many female activists, she encountered much hardship and antagonism. Another activist, Mah-Soltan Amir-e Sehhi, shared what these women had to struggle against: “The first problem was the unwillingness of landlords to lease a house for the school, which they imagined would be a center of corruption. After a house had been found and the landlord reassured, certain people in the locality began to stir up opposition and cause trouble. They…removed the school signboard or threw stones at it…neighbors used to get loiterers—very often psychopaths who then prowled the streets as there were no lunatic asylums—to walk into the school’s premises and grin at the terrified girls, while they themselves would gather outside the gateway to enjoy the spectacle and jeer. In reply to complaints from the school’s governors, they stated that the best way to avoid further trouble would be to close this “den of iniquity” and let no more girls through its gate.” Women’s education became a symbol of sexual corruption and the clergy accused schools of being centers of prostitution. Therefore, the founders of these schools, all of whom were women, made anxious efforts to justify educating girls. The selection of school names makes this clear: Namus (Honor), Effatiyeh (House of Chastity), Esmatiyeh (House of Purity) and Nasrotiyeh School for Veiled Girls. Tuba Azmudeh, like her activist counterparts, continuously received death threats and was denigrated as immoral. But eventually, Namus school expanded in size and curriculum and achieved prestige as progressive Iranians send their daughters to study there. Azmudeh later began to offer courses to adult illiterate women and has been credited with inspiring other female educators in Iran. She died in 1936 at the young age of 57. References:

Mastoureh Afshar (1898-1951 AD) was an Iranian intellectual and one of the pioneering women in the women’s rights movement. Mastoureh was born to an intellectual and open-minded family from Urmia, Azerbaijan in Iran. At a young age she mastered French, Russian and Farsi and later joined social and cultural movements that fought for the rights of women, such as the Society of Patriotic Women. With the 1905 Constitutional Revolution, many new societies and organizations were created and flourished. At the start of the revolution, female societies operated underground while aiding the revolution. Later, with the establishment of the parliament and the Second World War, some of those organizations began to officially operate and fight for women’s rights. The Society of Patriotic Women was one of those organizations. When Mastoureh became president of The Society of Patriotic Women, the Society had 200 members and its goals consisted of ensuring education for both girls and old women. The Society also supported orphaned girls and established a hospital for impoverished women. It published a magazine that fought for the rights of women and created a play called “Adam and Eve” which became immensely popular in Iran. Thousands of women, including European women, would attend the show. The money from the tickets was used to fund the education of old illiterate women. However, due to severe opposition from the Islamic clergy the play had to be shut down. Unfortunately, over time, with the accusation of having communist leanings, the Society was forced to close. Many of its female leaders, including Mastoureh, were later given the opportunity to join the Women’s Club, which was the very first female organization created by the government to assist women in need. Until the end of her life, Mastoureh fought for the rights of women. She died in September 1951 when she was only 65 years old. References:

Doctor Marzieh Arfaei (b. 1901) was the first woman to hold the rank of General in the Iranian military. She was born in Istanbul, five years before the Qajar King, Muzaffar el-Din Shah, reluctantly accepted the revolutionaries’ demands for a constitutional monarchy. Marzieh graduate from the Medical School in Istanbul in 1929 and for two years worked as a pediatrician and gynecologist. During her time away, Reza Shah overthrew the Qajar dynasty and worked on modernizing Iran. As part of that effort, he banned the veil and changed marriage laws, which clerics and conservatives in the society vehemently opposed. After returning to Iran, Marizeh worked as a physician for the Ministry of Health and was put in charge of two wards at the Pahlavi Hospital in Tehran. Eventually, she was appointed the Head of the Women’s Army school until the army hired her as a physician where she began to work in military hospitals. For many years, she also trained young women who wanted to become paramedics. In 1933, Reza Shah ordered that she be given the rank of Captain in Iran’s Imperial Army. After hard work and moving up the ranks, she was promoted to Brigadier-General by the order of Reza Shah’s son, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. Marzieh retired from the army in 1962 after serving for 30 years. She died in 1979 right before the success of the Islamic revolution and a regime that rolled back much of the progress made by women. References:

Maryam Amid Semnani who lived in the late 1800s to mid-1900s is known to be Iran’s first female journalist. This is at a time when reading and writing were not encouraged in women and in fact the King, Naser ed Din Shah Qajar, so did not like women to be educated that some of his wives hid their ability to read and write from him. Maryam Amid was the only daughter of the Shah’s physician, Mir Seyyed Razi Semnani, who took the education of his daughter in his own hands. Maryam Amid received primary education from her father and later on, continued her studies in French and photography. In 1910, she established the first magazine for women called “Science,” which though was shut down within a year, had a huge impact on society during the Constitution Revolution. Her second publication called Shokoufeh (Blossom) was made available in 1913 and became the largest dedicated newspaper for women. She also used the paper to fight superstition and traditional views held by many women. By condemning women’s traditional and underdeveloped attitudes and highlighting how women outside of Iran lived, especially in Europe, she increased Iranian women’s awareness in a lasting and fundamental way. She established a girl’s school called Mazineyeh. Due to conservative and patriarchal views of the society, families were hesitant to educate their daughters. Maryam Amid, therefore, came up with a brilliant plan. For every two students who signed up, one student could attend school for free, but then the parents could not pull out their daughters until the end of their studies. This plan was effective in encouraging girls to finish their education. Maryam Amid died in September 1919 on a trip to her hometown, Semnan, due to a heart attack. ----------------------------------------

References:

Farokhroo Parsa (1922-1980 AD) was Iran’s first female cabinet minister and an outspoken supporter of women’s rights in Iran. A physician and educator, she served as Minister of Education of Iran prior to the Islamic revolution. Farokhroo Parsa was born to a mother who was also a vocal proponent of gender equality and educational opportunities for women. In fact, the progressive views of her mother, Fakhr-e Afagh, who was the editor of a woman’s magazine called The World of Women, were met with opposition from conservative forces within the society, leading to the expulsion of her family by the government. Later with the intervention of Prime Minister Mostofi ol-Mamalek, her family was allowed to return to Tehran. Upon obtaining a medical degree, Parsa became a biology teacher at Jeanne d’Arc high school, where she came to know Farah Diba, one of her students, who later on would marry Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. In 1963, she was elected to the parliament and began to petition for suffrage for Iran’s women. She was also the driving force behind the legislation that amended existing laws concerning women and family. In 1968, she became Minister of Education in the cabinet of Amir-Abbas Hoveyda’s government. It was the first time in history of Iran that a woman had occupied a cabinet position. When the Islamic revolution occurred, Farrokhroo Parsa who had been out of the office for eight years, was arrested and charged with corruption and prostitution. According to Ms. Afkhanmi, Ayatollah Khomeini viewed all political participation by women as tantamount to prostitution. Farokhroo Parsa was executed by firing squad on 8 May 1980 in Tehran. In her last letter from prison, she wrote to her children. “I am a doctor, so I have no fear of death. Death is only a moment and no more. I am prepared to receive death with open arms rather than live in shame by being forced to be veiled. I am not going to bow to those who expect me to express regret for fifty years of my efforts for equality between men and women. I am not prepared to wear the veil and step back in history.” -------------------------------------------------------

Sources: Sadiqeh Dolatabadi was born in 1882 in Isfahan, Iran. Considered one of the pioneers of the Iranian women’s rights movement, she came from an old and established family. She started her education in Farsi and Arabic and later in life, attended Paris’ Sorbonne University, earning a degree in Education. In 1917, she founded the first girl school in Isfahan called “Maktab-e Shariat.” But the school was attacked by conservatives and clerics and was finally closed down, and she was thrown in jail. Two years later, she established the Society of Women of Isfahan and another school for girls who came from poverty-stricken families called “Om-ol Modaras” which ultimately had a very positive impact on women’s education. Dolatabadi was the founder of several publications including Women’s Voice which was banned by authorities. Her magazine only accepted submissions from women and most of its readers were women. In her magazine, she was highly critical of the veil and discussed controversial topics such as the rights of women to education and economic independence. When Reza Shah banned the veil in 1936, Sadiqeh Dolatabadi became an active supporter of the reform. Sadiqeh Dolatabadi died in July 30, 1961 at the age of 80. In her will she proclaimed: “I will never forgive women who visit my grave veiled.” After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Islamic vigilantes demolished her tomb, and the tombs of her father and brother, who, although men of religion, had supported her activities. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sources: |

Details

AuthorSaghi (Sasha) Archives

May 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed