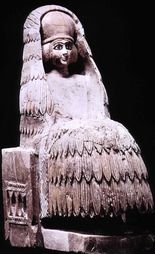

2500 BCE Veiled Priestess 2500 BCE Veiled Priestess  Veiled Greek Women Veiled Greek Women During the Hellenistic Empire women’s position improved as they interacted with Mediterranean cultures. The best documented one is that of Egypt. Egyptian civilization which had endured for several millennia had a remarkably liberal attitude toward women. Women in Egypt were not secluded, nor veiled, and they had equal rights to men. This shocked the conquering Greeks and over time Egyptian women lost most of their rights under European laws. [2] Evidence from the Christian era, such as the representation of women in garments concealing them from head to foot, points to the negative attitude toward women in early Christianity.  Veiled Christian Woman Veiled Christian Woman Evidence dating back from the Christian era, such as the representation of Syrian women in garments concealing them from head to foot, points to the negative attitude toward women in early Christianity. The shamefulness of sex was focused on the shamefulness of the female body which had to be concealed. Though Islam brought about a decrease in the status of women, Prophet Mohammad did not introduce veiling, nor did he make it compulsory. Though Islam brought about a decrease in the status of women, Prophet Mohammad didn't introduce veiling, nor did he make it compulsory. [2] In fact, the fierce independence of Prophet Mohammad’s first wife is well-documented. Khadija was a widow who was a successful merchant. She had hired Mohammad to oversee her caravans. She then proposed to and married him. Her way of life reflected the society of Arabia at that time. Veiling and seclusion were only observed by the Prophet’s later wives. According to Islamic scholars, the great descendant of the Prophet, Fatima al-Kubra, is reported to have invented a hairdo that she wore in public. She refused to cover her hair and is reported to have been imitated by other noble women. [3]. The veil was widely adopted only generations after the Prophet’s death. With the European occupation of North Africa and Near East in the 1800s and mid-1900s, the veil became the subject of much-heated debate. For example, Earl of Cromer, who was the British consul-general in Egypt used the veil to highlight the inferiority of Muslim societies, making them an open target for colonial attack. [2]  Lord Cromer Lord Cromer Ironically, while Cromer championed the unveiling of Muslim women, in England he was a founding member of the Men’s League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage. [4] In reaction to the European colonizers, secular rulers such as Ataturk of Turkey and Reza Shah of Iran, banned the veil, to push for modernization. This caused anger among the religious establishment as well as many women for whom appearing without a veil in public was tantamount to nakedness.  Iran - compulsory veil is enforced Iran - compulsory veil is enforced Over time, these aggressive actions backfired, because they weren’t based on reasoned analysis but rather a reaction to the colonizer’s perception of Islam. [5] With the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Iran's 1979 Islamic revolution, traditional conservative attire made a comeback as a method to fight Western imperialism. Now, Saudi Arabia requires women to cover their hair and wear full-body garments, while Iranian women are forced to cover their hair and wear a long coat called a manteau. And laws implemented by radical Taliban and Daesh punish women who do not adhere to their extreme vision of Islamic dress. These unreasonable regulations are enforced by religious police, causing great suffering for many women including lashes, acid attacks, abuse, rape, imprisonment and even execution. To justify their cruelty, extremists claim that they are simply following God's commands. But the Quran does not contain any words, which command women to cover their hair or entire body. Women's dress is addressed in two verses in the Quran. Verses 24:31 and 33:59. In 24:31 we are told, "And say to believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty; that they should not display their beauty and adornments except that which appears thereof; that they should draw their khumur over their bosoms and not display their beauty..." But what is khumur? Many Islamic jurists and scholars argue that khumur is a piece of cloth that covers a women’s entire body. Others argue that it’s a piece of cloth that covers the hair and the entire body except for the hands and face. The verse is often translated with added brackets that say “veil” or “head-covering” to mislead people. Linguistically, the word khumur means cover. Any cover—such as a table cloth, curtain or dress—and metaphorically, it can refer to a spiritual or mental state. [6]. Renowned Islamic scholar and jurist, Khaled Abou El Fadl, states that “The evidence that the khimar in pre-Islamic Hijaz covered the face or covered the hair is simply not there. The only thing that the verse allows us to say conclusively is that Muslim women were called upon to draw a piece of cloth (khimar) over the juyb (bosoms)—whether it covered the hair or the face, we don’t know. In other words, the Quran in this verse called upon women to cover their bosoms. Anything beyond that would require extensive research into the social practices of khimar dressing at the time of revelation, and the historical evidence is far more diverse and complex than many contemporary scholars assumed it to be.” [7] In the same verse, God commands women to not reveal their adornments (zinah) except “what appears thereof,” or what is normally shown. What is normally shown differs based on each person’s culture and environment. By leaving this guidance generic, God in His great wisdom, gives women the freedom to decide what they can and cannot wear, according to the time, place and occasion. [8] But many Islamic groups insist that with this verse, God issued a command for women to cover their entire body, head to toe, ignoring the fact that the word "hair" or "head" isn't found in this verse or anywhere in the Quran. The issue is that many contemporary jurists do not differentiate between awrah and zinah. In Islamic jurist literature, awrah refers to private parts that should be covered. In the Quran, the word awrah refers to something that is personal and should be hidden. And then there is the concept of fitnah, which is the notion that certain things produce sexual arousal and therefore is conductive to committing sin. The Quran refers to fitnah only in non-sexual ways, e.g. temptations such as money. However, in juristic terms, a woman’s awrah (private parts) have to be covered in order to not create fitnah. The most pronounced feature of today’s Islamic law is in fact its obsessive focus on fitnah. [9] As Fadl points out, in today’s Islamic law, “women are seen as walking, bathing bundle of fitnah.” [10] Essentially, jurists have decided based on a range of unreliable traditions and focusing on Quran commentary that the entire body of a woman is awrah (private parts), and by equating awrah to zinah (adornments), which is something a person adorns himself/herself with, they used Quranic verse 24:31 to say that all of a woman’s body is her private part and should not be shown. However, if God wanted a woman to cover her hair, He could have said, “Cover your hair with your khumur.” But he didn’t. If He wanted to say cover your entire body with khumur, He could have said that too, but He didn’t. He could have also clarified that zinah equals awrah which He clearly didn’t, because that wasn’t the original context of the verse. The same verse ends with, "And they should not stomp their feet lest they reveal that which they hide of their ornaments." Some Islamic scholars say that the reference to stomping feet has a historical context. There is a report that at the time, women of disrepute would wear ankle bracelets that made noise as they advertised their services. Either way, the reference to stomping feet is only teaching modesty [11] Also, before talking to women in this verse, the Quran addresses men. 24:30 asserts, “Say to the believing men that they lower their gaze and restrain from sexual passion.” By addressing men first, God is commanding them self-control. A man must reform himself first, rather than blame a woman for wearing what he-perceives-to-be provocative clothing. [12] Verse 33:59 says, “O Prophet, tell your wives and your daughters and the women believers to lower over them their garments (jilbab). This is more suitable that they will be known and not be abused or harmed.” A jilbab is an outer garment worn by men and women that covers unspecified parts of the body. According to classical scholars, the historical purpose of this revelation was to distinguish between free women and slave girls. In the next verse, 33:60, the Quran threatens men who harass women by saying that if the hypocrites and perverts in Medina do not desist from causing harm, they might be expelled from the city. Various sources say that at the time of the Prophet, scoundrels would hang out in the street and molest slave girls. It is clear by the very language of this verse that the purpose is to protect women. [13] As Fadl points out, “The clear majority of jurists conclude that the awrah of a free woman is all of her body except the face and hands. A minority conclude that all of a free woman’s body—including her face and voice—is awrah. Importantly, a clear majority conclude that the awrah of a slave girl is from her naval to her knee. For classical jurists, the issue was the social status of women. Free women were expected to cover their bodies; slave girls were not expected to cover their bodies except for the area between the knee and the naval. Very often when it came to working women, such as women in the bazaar, jurists would allow the women not to cover their hair or would content that women who had to make a living should dress in fashion that would not encumber their livelihood…. The fact that the vast majority of classical jurists set different expectations depending on the social position of women underscores the fact that customary law and social habits played a critical role in this field.” [14] If these rulings are truly from God, and the point is to protect women, why would He ignore the protection of poor slave girls? Clearly, these laws are man-made and local customs and social habits have been their driving force. By ignoring the historical context of this verse, Islamic jurists claim that a woman should cover herself with a jilbab, which they interpret as a long veil that covers her from head to toe. Besides, if God really wanted a woman to cover herself, He could have easily said lengthen your garment (jilbab) to your ankles or knees, but He didn’t. [15] And though the word hijab is used multiple times in the Quran, it is never in relation to women’s clothing, but rather as a partition or screen, such as between heaven and hell. The jurists also use hadiths, the sayings of the Prophet, to veil women. There is one hadith that says that the Prophet said, that once a woman reaches puberty, the only parts that may be shown are her hands and face. Another report says that in the last year of the Prophet’s life, women covered their heads so that they looked like “black crows.” Another commonly quoted hadith says that Aisha narrated that her sister Asma “visited the Prophet while wearing transparent clothing. The Prophet is said to have averted his gaze and observed that an adult woman must cover in public, except for her face and hands.” However, this hadith is highly controversial. Many scholars including Abu Dawud, the main transmitter of this report, agree that this hadith isn’t authentic, since the narrator from Aishah, Khalid b. Durayk, never actually met her [16]. Many scholars have pointed out that there are contextual and historical issues associated with these hijab hadiths. Fadl points out, “The problems we find with the hadith literature on this topic are mirrored by the range of juristic opinions on the issue of awrah…. Since there is no reliably dispositive hadith traditions and the classical juristic discourse is hinged on the social status of women, it forces us to focus on and give weight to the Quranic discourse about all else.” [17] Considering that classical texts on Islamic ethical conduct often discuss awrah as a moral value such as the avoidance of backbiting, it would be best if contemporary Muslims moved away from such mechanical interpretation of the sacred texts and focused more on pursuing ethical qualities of humility and dignity. [18] Though veiling predates Islam and there is nothing uniquely Islamic about it, modern Muslims have chosen, since the 1970s to make it an integral component of identity politics. If you are a Muslim, who insists that women should cover their hair or body, you must ask yourself: Why do I feel it necessary to control women? Is it a woman’s fault that I, as a man, cannot control my desires? God has given us the ability to make our own choices and live with their consequences. Ask yourself, if God gives women choices, who am I to defy Him and take away a woman’s choice? And ultimately whether a woman chooses to wear a veil or not, should be her choice—not that of radical groups, jurists, secular governments, her family or anyone else. Islam tells us that seeking knowledge is one of the greatest acts of worship. As women, we too are rays of God’s light and can tap into that wisdom [19]. We must understand the origins of Islamic laws so that we can defend our right to choose. In the words of Ibn Arabi, “She who knows herself, knows God.” Know your inherent beliefs. ------------------------------------------------- Here is only a sample of Islamic scholars who have said that the Muslim veiling (hijab) is not mandatory or an obligation:

------------------------------------ References: 1. Mohja Kahf, “From Her Royal Body the Robe Was Removed: The Blessings of the Veil and the Trauma of Forced Unveilings in the Middle East,” in Jennifer Heath, Ed., The Veil: Women Writers on Its History, Lore and Politics (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008) 2. Ahmed, Leila. "Women and Gender in Islam." Yale University Press. 1993; "Veil." Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. 3. Abou El Fadl, Khaled. Fatwa on Permissibility of not Wearing Hijab. Issues 12.31.2016. 4. Ahmed, Leila. "Women and Gender in Islam." Yale University Press. 1993; "National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage." Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. 5. Ahmed, Leila. "Women and Gender in Islam." Yale University Press. 1993; Mohja Kahf, “From Her Royal Body the Robe Was Removed: The Blessings of the Veil and the Trauma of Forced Unveilings in the Middle East,” in Jennifer Heath, Ed., The Veil: Women Writers on Its History, Lore and Politics (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008) 6. Abou El Fadl, Khaled. "Speaking in God's Name: Islamic Law, Authority and Women." OneWorld. Oxford. 2003. pp 108; Shafti, Farhad. Implication of the Word Khimar for Hijab. March 2013. Journal: Exploring Islam; Moiz, Amjad. Regarding Head Covering for Women. 2003. Understanding Islam; Quran-Islam.org "Dress Code for Women; Syed, Ibrahim B. "Misinterpretation of Quranic Verses on Hijab." Islamic Research Foundation International, Inc. 7. Abou El Fadl, Khaled. Fatwa on Permissibility of not Wearing Hijab. Issues 12.31.2016. 8. Quran-Islam.org "Dress Code for Women; Abou El Fadl, Khaled. "Speaking in God's Name: Islamic Law, Authority and Women." OneWorld. Oxford. 2003. 9. Mir-Hosseini, Ziba. "Hijab and Choice: Between Politics and Theology", in Mehran Kamrava (ed..), Innovations in Islam: Traditions and Contributions, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011; Abou El Fadl, Khaled. "Speaking in God's Name: Islamic Law, Authority and Women." OneWorld. Oxford. 2003; 10. Abou El Fadl, Khaled. "Speaking in God's Name: Islamic Law, Authority and Women." OneWorld. Oxford. 2003 11. Abou El Fadl, Khaled. Fatwa on Permissibility of not Wearing Hijab. Issues 12.31.2016. 12. Qasem. Rashid. "Muslim men need to understand that the Quran says that they should observe hijab first, not women." Independent. March 2017. 13. Hasan, Usama. "The Veil: Between Tradition & Reason, Culture and Context." First publiched in Islam and the Veil, ed. T. Gabriel & R. Hannan, Continuum, 2011; Abou El Fadl, Khaled. Fatwa on Permissibility of not Wearing Hijab. Issues 12.31.2016. 14. Abou El Fadl, Khaled. Fatwa on Permissibility of not Wearing Hijab. Issues 12.31.2016; Mir-Hosseini, Ziba. "Hijab and Choice: Between Politics and Theology", in Mehran Kamrava (ed..), Innovations in Islam: Traditions and Contributions, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011. 15. Quran-Islam.org "Dress Code for Women 16. Hasan, Usama. "The Veil: Between Tradition & Reason, Culture and Context." First published in Islam and the Veil, ed. T. Gabriel & R. Hannan, Continuum, 2011 17. Quran-Islam.org "Dress Code for Women; Abou El Fadl, Khaled. Fatwa on Permissibility of not Wearing Hijab. Issues 12.31.2016.; Hasan, Usama. "The Veil: Between Tradition & Reason, Culture and Context." First published in Islam and the Veil, ed. T. Gabriel & R. Hannan, Continuum, 2011 18. Abou El Fadl, Khaled. Fatwa on Permissibility of not Wearing Hijab. Issues 12.31.2016 19. For instance, refer to the great Islamic philosopher and the founder of the Philosophy of Illumination, Suhrewardi's "Ontology of Lights." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Other sources referred to: Jahangir, Junaid. “5 Muslim Scholars on the Permissibility of not Wearing the Headscarf.” Huffington Post. 2017; Duderiga, Adis. “Why Muslim Coverts Wear Hijab.” New Age Islam. 2012.; Abdallah, Myra. “The sheikh who lifted the veil.” NOW. 2014. Comments are closed.

|

Details

AuthorSaghi (Sasha) Archives

May 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed