|

Bibi Khanum Astarabadi (1858-1921 AD) was one of the pioneering figures in Iran’s women’s rights movement. She was born to Mohammad Baghar Khan Astarabadi, a military commander, and Khadijeh Khanum, a companion to one of Nasser al-Din Shah’s favorite wives. At the age of 22, she married and had seven children, most of whom grew up to make a name for themselves. It is through her love for education and the founding of the first school for girls that Bibi Khanum is best known. In 1906, with the excitement surrounding the Constitutional Revolution, Bibi Khanum succeeded in getting the consent of authorities for opening a girl school. To address the religious sensitivities of the time, she assured parents that all teachers were women and no other man—except for an aged doorman—would be in school. However, Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri, a mullah who later sided with anti-Constitutionalists and was eventually hung following a civil war, issued an edict saying girl schools were against Islamic law, and another cleric published a pamphlet that stated, “Pity the country which has girl schools.” This prompted a group of men to attack the school and break its windows while the girls were in class. Bibi Khanum temporary closed down the school but did not give up and the following year opened a new one. Bibi Khanum was also a satirist. When in 1895 AD, an anonymously-written booklet called “The Edification of Women” was written by a Qajar prince, she decided to write a rebuttal to it. The booklet was a crude manifesto of patriarchy and was published at a time when society was becoming more exposed to Western ideals. It said that among other things that a woman is like a child and should be educated by a man, she must not speak during meals and walk slowly, like an ailing individual. Bibi Khanum called her book “The Imperfections of Men” and used satire to get her point across. She wrote, “To sum, yours truly does not believe that she is able to edify men, so I wrote [this book] to disclose their shortcomings so that perhaps they would stop trying to educate women and instead edify themselves.” ----------------------------------------------------

Sources:

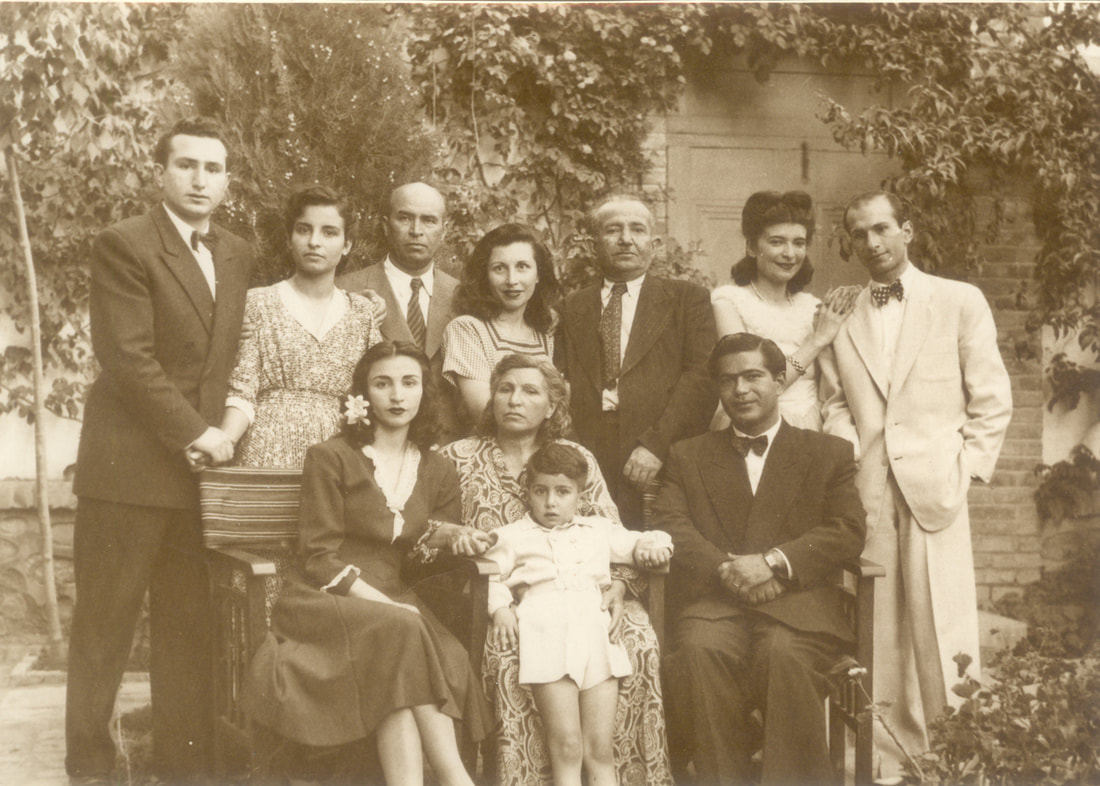

Iran Dokht Teymourtash (1914-1991 AD) is considered a pioneer among Iranian women. She is known to be the very first woman to appear in public unveiled when delivering the commencement address for her graduating class in 1930, several years before Reza Shah banned the veil. Her father was Abdol Hossein Teymourtash, one of the most influential Iranian politicians who served as the first Minister of Court of the Pahlavi dynasty and is credited for laying the foundations of modern Iran in the 20th century. Impressed by the breadth of his knowledge, an American representative in Tehran, once said, “…the man’s gifts were extraordinary as to appear unnatural. Whether it was foreign affairs, the construction of railways…, educational administration or finance, he, as a rule, could discuss those subjects more intelligently than the so-called competent ministers.” He spoke fluent Farsi, French, Russian and German and had strong command of English and Turkish. However, finally, while attempting to revise the terms of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company which retained near monopoly control over the industry in Iran, he managed to anger the British who did not want to give up power and control. Due to his powerful position he had created enemies, and many believe that the British had a hand in forging documents to convince Reza Shah that Abdol Hossein was a traitor and Soviet spy. He was ultimately arrested and killed in prison and his family forced into years of exile. After the Allied occupation of Iran and Reza Shah’s own exile, the Teymourtash family returned to Iran. Iran Dokht who had inherited her father’s strength of character, traveled to Iraq to avenge her father. She succeeded in arranging for the extradition to Iran of the person believed to have killed her father, Doctor Ahmadi, who was subsequently tried and sentenced in Tehran for having arranged the murder of various individuals in Qasr prison. Iran Dokht also served as the first female editor of an Iranian newspaper and earned a PhD in philosophy and literature while residing in France. Despite Mohmmad Reza Shah’s attempts at reconciliation, and even giving her the opportunity to briefly serve as the press attaché at the Iranian embassy in Paris, she never became close to the royal court again. Though briefly engaged to Hossein Ali Qaragozlu, Iran Dokht never married. She passed away in 1991 in France. ----------------------------------------------

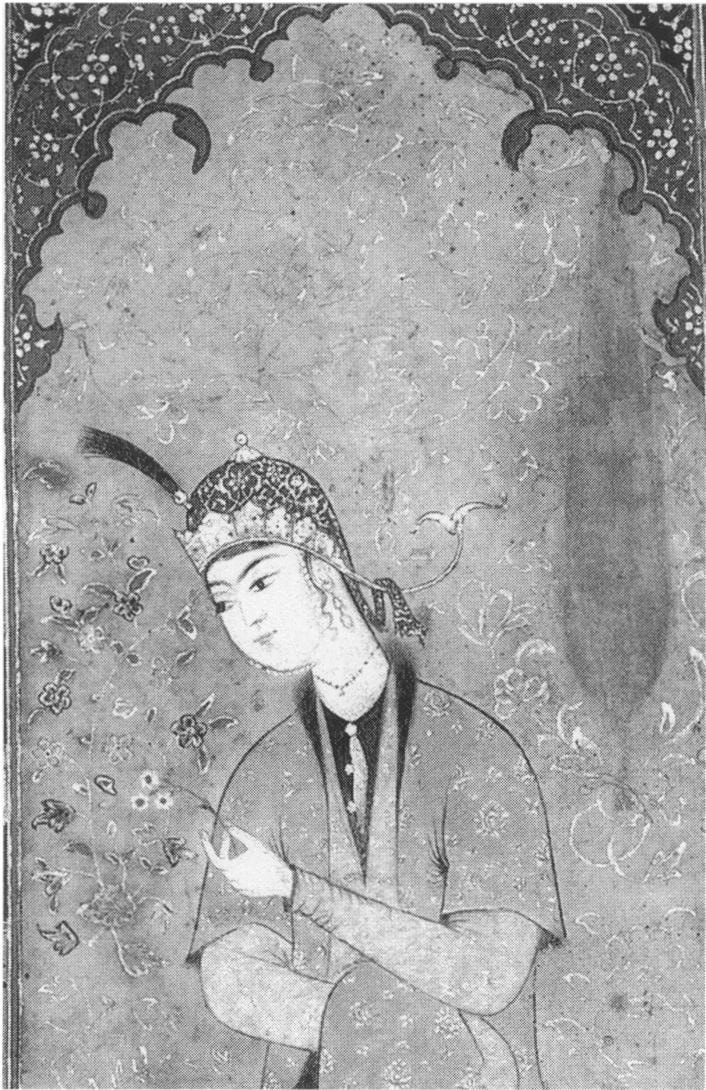

Sources: * "Iran Teymourtash" Wikipedia CC SA BY 3.0 (English and Farsi versions) * "Abdolhossein Teymourtash" Wikipedia CC SA BY 3.0; Photo: Iran Teymourtash Pari Khan Khanum (1548-1578 AD) was a well-known princess and the daughter of Tahmasp, the Iranian Safavid Shad. Highly educated in Islamic sciences and an accomplished poet, she proved herself to be an influential politician. Though engaged, she never married, preferring the bureaucratic life in the capital. When Shah Tamasp became ill without choosing a successor, the powerful Qizilbash, who had brought the Safavid monarchs to power, had to decide who should rule next. Some favored Haydar Mirza, the Shah’s third son, while others including Pari Khan Khanum favored another son, Ismail Mirza, who wrongfully accused of treason had been imprisoned by his father. In their eagerness to bring Haydar Mirza to power, his supporters tried to kill Ismail Mirza in prison but Pari Khan Khanum uncovered the plot and sent a group of musketeers to safeguard him. Two years later, the Shah died and Haydar Mirza prematurely announced himself king, creating a series of events that finally led to his downfall. Attacked by his brother’s supporters, he took Pari Khan Khanum as hostage in the palace. She convinced him to release her, promising him her support. But upon release, she broke her oath and opened the gates to his enemies who finally killed him. As the supporters of the brothers struggled for the throne, Pari Khan Khanum became the de facto ruler of the country. The chieftains of all clans took orders from her—whether fiscal, financial or political. And it was she who ordered top ranking members of the realm to gather and confirm Ismail Khan as the new Shah. But Ismail Khan showed her no gratitude. After being in prison for almost 19 years, he had become a bitter angry mad who did not like his authority questioned. He forbade officials to visit Pari Khan Khanum’s palace, dissolved all her duties and seized her properties. Furious at his behavior after the support she had given him, she planned her revenge. A year later, Ismail Khan died abruptly, and the court physicians announced that he was poisoned. The Qizilbash decided to pass the crown to Khodabandah, Ismail Khan’s older brother, who was nearly blind and unfortunately also quite incompetent. The agreement was that he would remain Shah in name only while Pari Khan Khanum ruled. However, over time, weary of her incredible influence, the Qizilbash decided to put an end to her rule. One day while she was walking home, she was seized and strangled. Thus, ended the rule of one of Iran’s most powerful female politicians. -----------------------------------------------------------------

Sources:

Alenush Terian (1920-2011) was an Iranian-Armenian astronomer and physicist who has been called “The Mother of Modern Iranian Astronomy.” In 1947, Alenush graduated from the Faculty of Science at the University of Tehran and went to work in the physics laboratory of the university. A year later, she was elected the Head of Operations of the laboratory. She signed up for a scholarship to further her studies in France but was not accepted because she was a woman. This did not deter her from going to Paris with her father’s financial support. She studied at the Faculty of Atmospheric Physics of the Sorbonne and obtained a PhD in 1956. Though she was offered a job there, she rejected it with the aim of bringing her services to Iran. She came back and became assistant professor of Thermodynamics at the Faculty of Physics in Tehran University. In 1964 she received the grade of full professor and became the first female Professor of Physics in Iran. In 1966 she became a member of the Geophysics Committee of Tehran University. Soon, she was named elected Chief of the Solar Physics studies at the University and worked in the Solar Observatory of which she had been one of its founders. She retired in 1979. She did not marry and devoted her entire life to her studies and students. As one former student said, “She always said that she had a daughter called Moon and a son called Sun.” Alenoush Terian passed away in March of 2011. She left her home to the Armenian community and to those students who do not have a proper place to live. --------------------------------------------------------------

Sources: In the pre-Islamic Iran, not only were there female rulers and warriors, but women became guardians of disinherited sons, and went to court on behalf of and against their husbands. So, though Islam brought revolutionary legal rights for women in Arabia, it did not elevate the position of Iranian women, and in fact eliminated some of the existing rights and customs to the detriment of Iranian women. After the Islamic conquest of 651 AD, women in Iran never again participated in politics officially nor ruled directly. However, the situation got worse after the Safavid dynasty (1501-1736 AD) moved away from Sufism and established Twelver Shiism as the state-sponsored religion of the country. Reports by Italians travelers indicate that at the beginning of the Safavid reign, women were neither veiled nor secluded. In the Italian account of the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 AD between Ottoman Sultan Selim and the first Safavid Shah Ismail, it has been reported that “The Iranian ladies themselves follow in arms the same fortunes as their husbands, and fight like men....” Another account by the Venetian Michele Membre who went on a mission to the court of the Safavid says, “The Shah’s maidens pass on fine horses; and they ride like men and dress like men, except that on their heads they do not wear caps but white kerchiefs...and they are beautiful.” As an example, Tajlu Khanum, one of Shah Ismail’s wives, is reputed to have been an able fencer and wrestler who participated in the battle of Chaldiran. However, 100 years later, as the Safavids became more orthodox, and made Twelver Shia the state-sponsored religion, women began to lose their remaining rights. During the reign of Shah Sulayman (1667-94 AD), Sir John Chardin reports Iranian women to be totally secluded and veiled. The head-to-toe covering by then had become a custom and continued throughout the Qajar era to this day. The veiling and secluding occurred because of Shia clergy’s orthodox interpretation of the Islamic position on women, which superimposed itself completely upon all past customs and traditions. Subsequently, the role of women became that of a housekeeper, bringing up children and providing the husband with sexual and culinary pleasure. ---------------------------------------------------------

Sources:

Forough Azarakhshi (1904-1963 AD) established the first elementary and secondary schools for girls in Mashhad, Iran. The school which would later be known as Forough’s school, had a tremendous impact on the education of women in Iran. Like most Iranian women who dared to break barriers, Forough Azarakhshi received death threats from Islamic extremists and conservatives within her society. There were even those who threatened to burn down the school. In a show of strength, her family, including women, took up arms and protected the school for two years. Despite the threats, Forough never closed the school nor canceled any of the classes. There are many women in the religious city of Mashhad who to this day remember Forough Azarakhshi fondly and speak of her with utmost respect. Forough financed the school with her own savings, but over time, as budget became an issue, the government began to provide financial support. One of her students was Farokhroo Parsa who would one day become not only a physician but the first female cabinet minister prior to the 1979 Islamic revolution. Forough was also President of the Children Orphanage of Khorasan, of the Association for the Protection of Mothers and Children, and the Charity Commission. She also became the honorary president of the Red Lion and Sun Society of Iran in Mashhad. ---------------------------------------------------

Sources: In 1910, the French Raymonde de Laroche, became the world’s first licensed female pilot. Seven other French women followed her, earning pilot’s licenses within the next year. Iran followed suit. In 1925, Reza Shah, formed the Iranian Aero Club and in 1939 began to advertise for prospective pilots. 630 young people signed up and to the surprise of the club officials 22 of them were women. Out of those women, 7 were admitted into the club and only three passed the requirements to join. These three were Effat Tejaratchi, Ghodsieh Farokhzad Naraghi and Ina Ushid, who would become the first Iranian female pilots. Effat Tejaratchi’ story is the best documented. She had a dream of becoming a pilot. When she saw the Aero Club’s advertisement she was excited, but then she realized that no other woman had ever done this before. Intimidated she went home and told her father about it. He had intervened. “What is wrong with you becoming the first Iranian female pilot?” he had asked. With his encouragement Tejaratchi had returned to the club and was surprised that the Officials of the Club praised her for applying, and the press applauded her. She became the first to qualify for a solo flight in 1940. She piloted a DH-82 Tiger Moth. She was only 23 at the time. With the Second World War and the Allies forcing Reza Shah into exile, the Aero Club was also abandoned. It was only after the war, with the encouragement of her husband, that she returned to the Iranian Royal Air Force as a flight officer. She eventually became the Director of the Club until the 1979 Islamic revolution. ---------------------------------------

Sources: Why Iran does not ratify CEDAW? The Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) was formally adopted on 18 December 1979 by the United Nation General Assembly. CEDAW requires compliance by governments to ensure equality between men and women and eliminate discrimination against women. Countries that have ratified CEDAW are legally bound to put its provisions into practice. They are also committed to submit reports regularly on measures they have taken to comply. More than 90% of the countries are a party to this convention from which 51 countries are from the Islamic world including Tunisia and Morocco. Yet, there are a few countries, Iran among them, that have not ratified the convention. Iran’s reasons include the government’s belief that the human rights doctrine is not universal but derived from European Enlightenment philosophy and so does not apply to an Islamic society. There are huge contrasts between CEDAW and Iran’s current Constitutional Law which is highly discriminatory toward women. Iranian officials did discuss twice to ratify CEDAW. Once in 1995-1997 during the presidency of Rafsanjani who believed that the economic and social construction of the country took priority over women’s rights and so the ratification never gained momentum. CEDAW also re-emerged between 1999-2003 during the presidency of Khatami. However, the Guardian Council, which is charged with approving legislation rejected the bill. This is not a government that supports equality between women and men. This view has resulted in extreme discriminatory practices affecting Iranian women. Women continue to be treated as second class citizens. For example, a woman’s testimony is worth half of a man’s in court. Women must wear compulsory hijab, and within the family, husbands can legally control whether their wives can have jobs or obtain a passport. This of course has to do with the extreme interpretation of Islamic scripture by the government, and the fact that women’s rights in Iran are in conflict with the interests of a predominately male leadership in a patriarchal society. ---------------------------------------------- Sources:

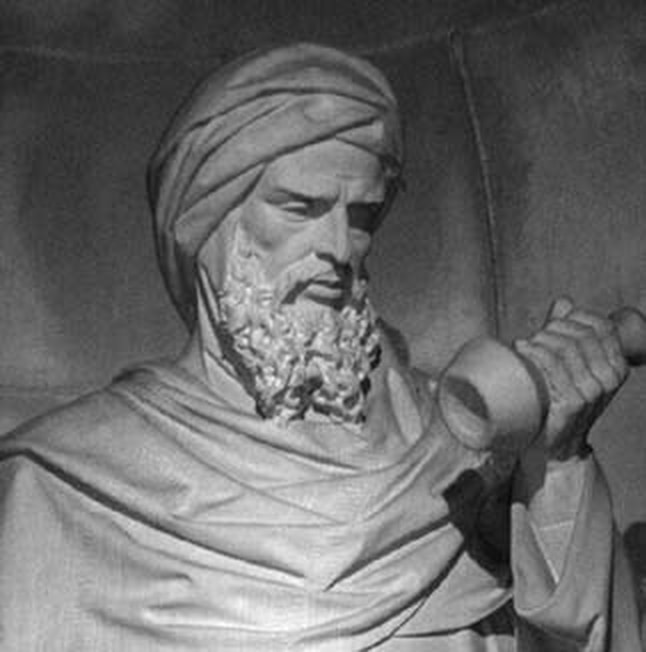

To understand how science was sidelined in Iran, and indeed all Near East, one must learn about the great Muslim philosopher, Averroes (1126-1198), and his rebuttal against the Iranian theologian, Ghazali (1058-1111). Until the 19th century, there was no distinction between scientists and philosophers and many of the great philosopher-scientists in the West were also theologians while in Iran they were often mystics. The creation of science began with the split between Platonism and Aristotelianism. Plato is often called the Father of Philosophers and Aristotle the initiator of the scientific method. Averroes (Ibn Rushd) was a Muslim Andalusian philosopher-scientist who became famous for his commentaries on Aristotle. He was ultimately responsible for re-awakening Europe to ancient Greek philosophers, an area abandoned during the European dark ages. But while in the West philosophy was slowly embraced, in the Muslim world it was sidelined. In the 13th century, the domination of Near East by Seljuqs led to the eclipse of philosophy as the Seljuq leaders preferred the teaching of the Quran to schools of philosophy. The most important attack against philosophers came from the Iranian Sufi theologian, Ghazali. In his book, “Incoherence of the Philosophers” Ghazali diminished views of scientists such as Avicenna, accusing them of deviating from Islam. His book became immensely popular, setting the stage for anti-scientific thought in the Muslim world. It was during this bleak ear of decline, that Averroes emerged as one of the last influential Spanish-Muslim philosophers. In his book “Incoherence of Incoherence,” he challenged the anti-philosophical sentiments sparked by Ghazali—a critique that ignited a similar re-examination within the Christian tradition, influencing scholars who would later be identified as “Averroists.” But Averroes was not able to change the course of history. Eventually, he was publicly insulted, cursed and accused of heresy by King Mansur’s (1184-1199) court and the King ordered him to be exiled and to burn all philosophical books except those dealing with medicine, mathematics and astronomy—these books he said were important because they help people know the time and direction of Mecca. Islamic philosophy came to a sudden halt in the West, but philosophical thought did not completely disappear from Iran. It took refuge in philosophical Sufism and philosophical theology instead, but the rational thought process that would one day lead Europe to the scientific progress we see today was immensely diminished. ---------------------------------------------

Sources:

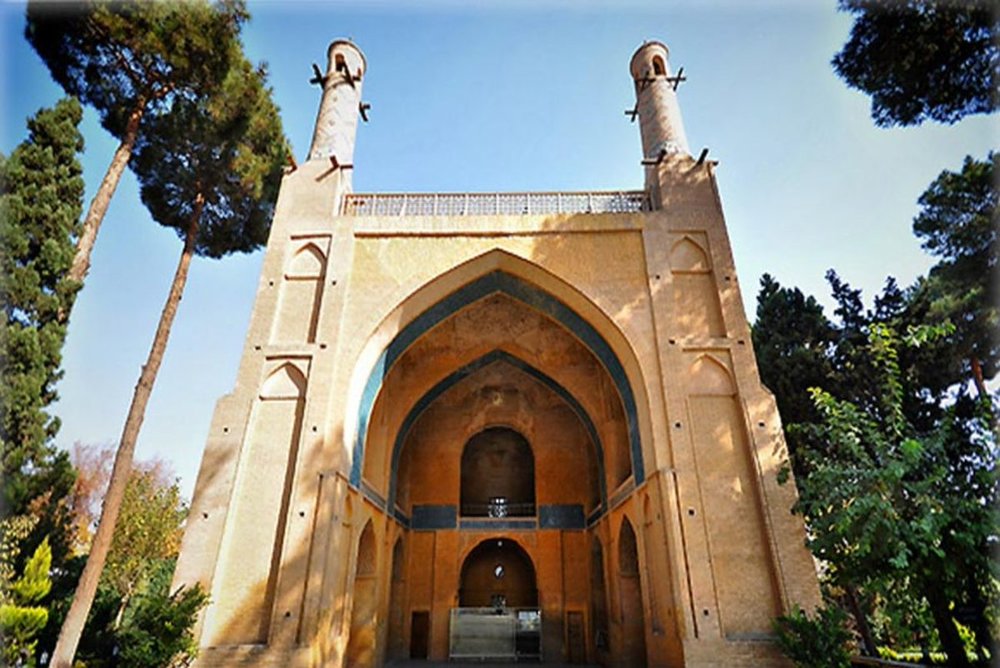

Sheikh Bahai (1547-1621 AD) was a scholar, philosopher, architect, mathematician, astronomer and poet in 16th century Iran. He was born in Lebanon and migrated in his childhood to Safavid Iran with his father. He wrote 88 books on philosophy, logic, astronomy and mathematics. He had Sufi leanings, often dressing like a Dervish and joining Sufi circles, specifically the Nurbakhshi and Nimatullahi Sufi orders. He was one of the main founders of the Isfahan School of Philosophy and drove the design of several monuments such as Monar Jonban (Shaking Minarets) in Isfahan. He was also an expert in topography, directing the water of the Zayandeh River to different areas of Isfahan and designing a canal called Zarrin Kamar which is one of Iran’s greatest canals. He also constructed a furnace for a public bathroom which was open to the public until 20 years ago. Interestingly, the furnace was warmed only by a single candle, which was placed in an enclosure, warming the bath’s water. For centuries, the unsolved mystery of the bath preoccupied scientists around the world. Known as the “mysterious bath” because it was warmed without the use of a direct energy source, the heating system was considered an engineering masterpiece. When recently repair work was done in Sheikh Bahai’s house, clay pipes and connected wells were discovered on the floor of a building next to it, shedding light on where the energy of the candle comes from. Archaeological studies revealed that the sewage system in Isfahan was connected to the bath through pipes. Scientists have said that the heat stemmed from its water container (boiler) which is made of gold,, which is a perfect conduit of heat and electricity, generating vast amounts of energy with low amount of heat. As to why Sheikh Bahai refused to reveal the secrets of the bath’s heating system, some say it might have been due to concern about thieves attempting to steal the gold in the bath had they known about it. -----------------------------

Sources: |

Details

AuthorSaghi (Sasha) Archives

May 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed